Last year, 2020, marked an outbreak of the gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae) in Ontario. The gypsy moth heavily defoliates mostly deciduous trees such as maple, oak, willow, birch, beech, aspen, apple, poplar, some conifers and more during an outbreak. Outbreaks occur cyclically, the population peaking every 7-10 years or so.

The gypsy moth maintains a relatively innocuous low level existence between peaks when all is in balance. This is thanks to the work of it’s natural enemies: pathogens, parasites and predators. A lower level of gypsy moth infestation is predicted for this year, 2021, because of natural enemies responding to last year’s peak outbreak.

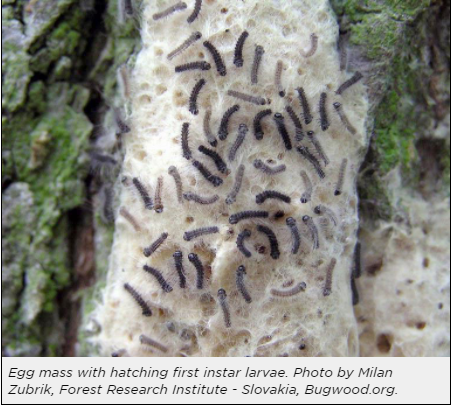

Although the gypsy moth was introduced from France to North America, Massachusetts, in 1869, it did not appear in Ontario until 100 years later. The primary means of long range dispersal is through transport of the egg masses, hence the name. The females do not fly. Egg masses are plastered to surfaces late summer to fall protected with a dense layer of tan coloured hairs from the female’s abdomen:

Watch for egg masses on surfaces varying from trees, branches, bark, firewood, outdoor furniture and outbuildings, playground equipment, under eaves to vehicles and trailers, boats, in wheel wells and underneath bumpers. Scrape off the egg masses and drop them into soapy water.

They ‘balloon’ climbing to the tips of branches then dropping into a breeze by silken threads which can carry them considerable distances on a windy day.

There are 5 and 6 larval instars, male and female, respectively. The growth of each instar is about one week each depending on temperature and instars are delineated by moults. By the 4th instar larvae conspicuously alter behaviour migrating down trees to hide in cracks, crevices and leaf litter at night then returning to the tree canopy to resume feeding next day. This is the best time to trap them using the burlap skirt method. Note the characteristic 5 rows of blue spots in identifying later instar larvae:

Late instar larvae finally pupate at or near ground level in July and many will be consumed if there are healthy populations of predators.

Natural enemy populations typically follow the peaks and troughs of the:ir host population so, unless your area was indiscriminately sprayed with broad spectrum pesticides you should be seeing evidence of last year’s natural enemy control against gypsy moths this year through overall reduced defoliation.

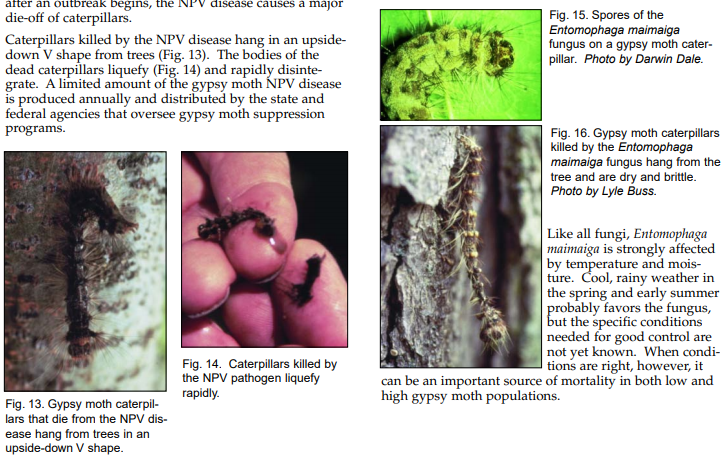

A nuclear polyhedrosis virus (NPV) is evidenced by dead caterpillars seen on the tree in an upside down ‘V’ position. A fungal pathogen, Entomophaga maimaiga, is characterized by dead caterpillars which dessicate on the tree in a vertical position. Both of these pathogens are effective in long term control of the gypsy moth:

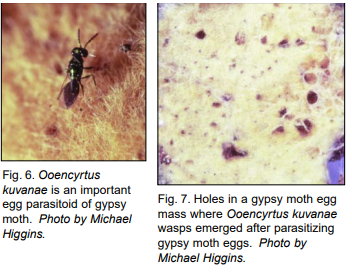

A tiny chalcidoid wasp introduced in 1908, Ooencyrtus kuvanae, attacks gypsy moth egg masses and is effective in gypsy moth outbreak collapse. Tiny wasps emerge from the egg masses instead of moth larvae leaving telltale pin-holes:

Bacillus thuriengensis kurstaki is a bacterial pathogen effective in control of later instars of gypsy moth, however, all moths and butterflies are susceptible, not just pest species.

Diverse wildlife is important in flattening peaks of gypsy moth populations and for long term control. Despite the caterpillars bristling with defensive urticating hairs that not all potential predators are prepared to tackle (wear gloves if you plan on handling them and don’t rub your eyes!) several birds prey on various stages of the gypsy moth including blue jays, orioles, robins, chickadees, woodpeckers, grackles, starlings and more. Small mammals such as mice, shrews, moles, chipmunks, skunks, raccoons, opossums and more have adapted to feasting on the different stages of the gypsy moth. Amphibians and reptiles will feed on adults, larvae and pupae. Toads are voracious predators of the gypsy moth.

Unless something better, easier, presents itself many gypsy moth predators will expend the energy needed to feed on larval stages with their urticating hairs in some cases by skinning the caterpillars.

Arthropod predators include ants, harvestmen (daddy-long-legs), spiders, wasps and beetles. The carabid beetle, Calosoma sycophanta, was introduced in 1906 to augment natural control efforts against the gypsy moth. It demonstrates remarkable specificity for a predator because it’s life history is so closely synchronized with that of the gypsy moth:

What can you do?

Natural enemies of Lymantria dispar can be encouraged and protected by fostering their natural habitats. Permit leaf litter and loose bark, for instance, as it provides safe shelter and hiding places. Do not feed wildlife or they will quit foraging but do ensure they have a consistent supply of fresh water to maintain them in your area.

Avoid the use of broad spectrum and toxic chemical pesticides.

Learn to recognise the stages of the gypsy moth.

Make it a matter of routine to check your vehicle, trailer, boat, firewood, etc. before heading out on a trip for egg masses late summer to early spring and scrape them off into a bucket of soapy water.

As I write this May 23rd in Orillia egg masses are hatching; a 5 mm early instar larva was ballooning swinging from a thread of silk in the breeze at my back door. They use the threads to disperse after hatching then will remain high in the canopy of the tree they drift to, feeding and shedding to progressively larger instars as they feed. You can spray water through the foliage and/or shake the tree to dislodge the early instars. They will have difficulty returning to the tree and may be consumed by predators. After the 3rd instar gypsy larval behaviour changes. This is the best time to take more action:

Create a burlap skirt to trap later instar larvae that have developed the behaviour of migrating from the tree canopy to the ground each night. Fold a length of burlap in half lengthwise then tie it around the tree with string chest high. Larvae become trapped in the burlap during the night then can be dispatched into soapy water the next day. If you opt to plunge the caterpillar laden burlap into soapy water instead of picking them off (wear gloves and keep out of domestic laundry facilities!) then rinse it well and hang to dry before wrapping the tree again. The trap needs to be checked each day for best control as larvae can eventually work their way out from the burlap.

Do not use sticky bands which indiscriminately and permanently trap whatever comes close including birds and small mammals that are predators of the gypsy moth. The results can be devastating.

A healthy tree can recover from an onslaught of Gypsy moth defoliation. Heavy defoliation over consecutive years, however, can kill the tree. The key to living with this pest in the long term lies in moderating it’s outbreaks to manageable levels, flattening the curves. The gypsy moth will never be eradicated but it has lived in northeastern North America long enough to become naturalized. There is a plethora of native wildlife that have adapted to the gypsy moth here in Ontario plus the very early introduction of a few of gypsy moth’s natural enemies from Europe, continue to be effective. The secret to moderating gypsy moth outbreaks and long term control lies in fostering natural enemies to work their magic.

REFERENCES and PHOTOS

https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/pest-control-tips/gypsy-moths.html

Calasoma sycophanta: A natural enemy of gypsy moth larvae and pupae. 2001. Michigan State Univ, Extension Bulletin E-2622.

Natural Enemies of Gypsy Moth: The GoodGuys!. 1999. Michigan State Univ, Extension Bulletin E-2700.

Gypsy moth: Information about gypsy moth (Lymamtria dispar dispar), a forest defoliating insect. 2021. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry www.ontario.ca .

Gypsy Moth Handbook: Predators of the Gypsy Moth. 1974. USDA Handbook No. 534.

Weseloh, Ronald M. 2003. People and the gypsy moth: A story about human interaction with an invasive species, AMER ENTOMOL 49(3): 180-190.